True, for Alan Turing, honours “a man who was pivotal in changing the course of all our lives.”

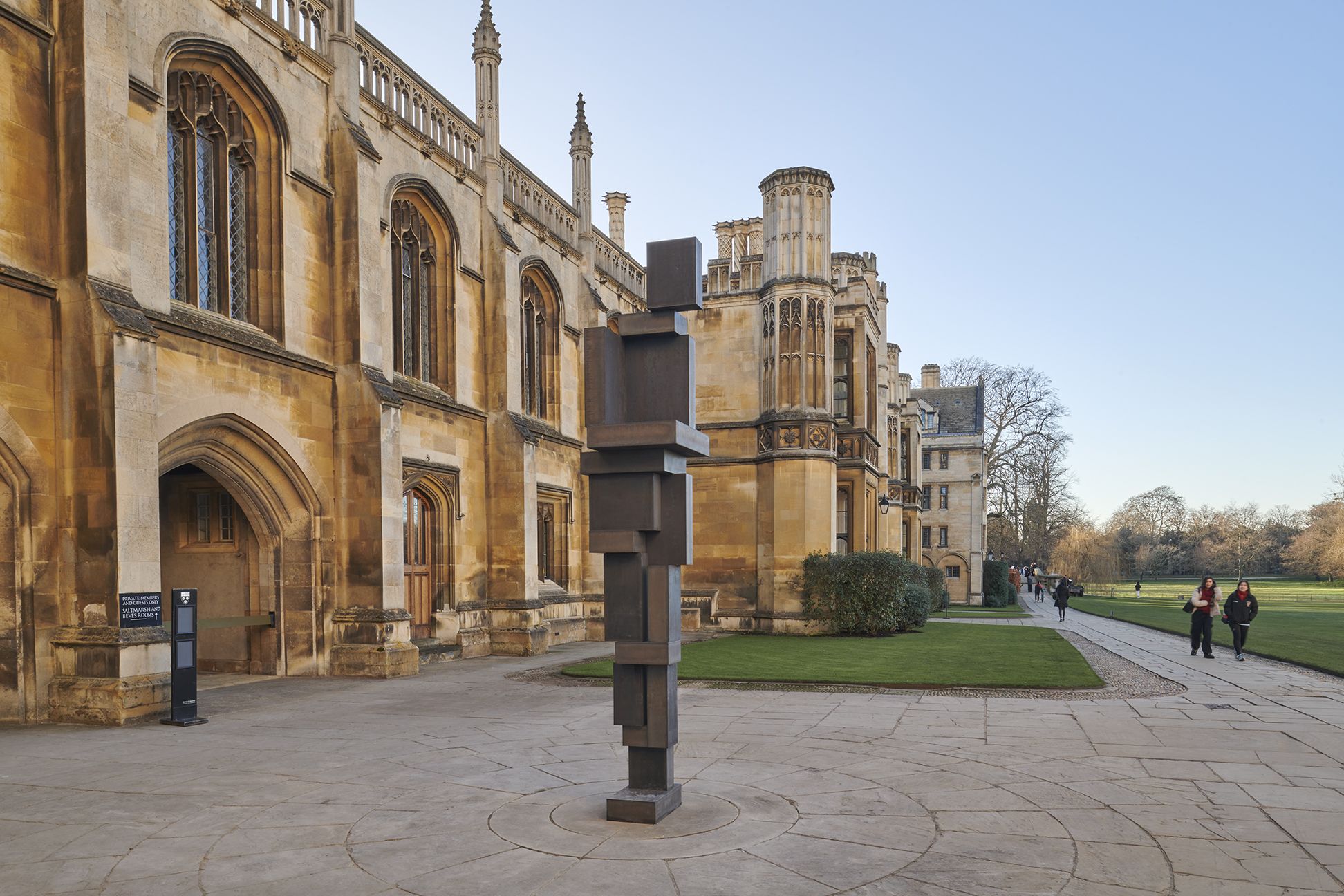

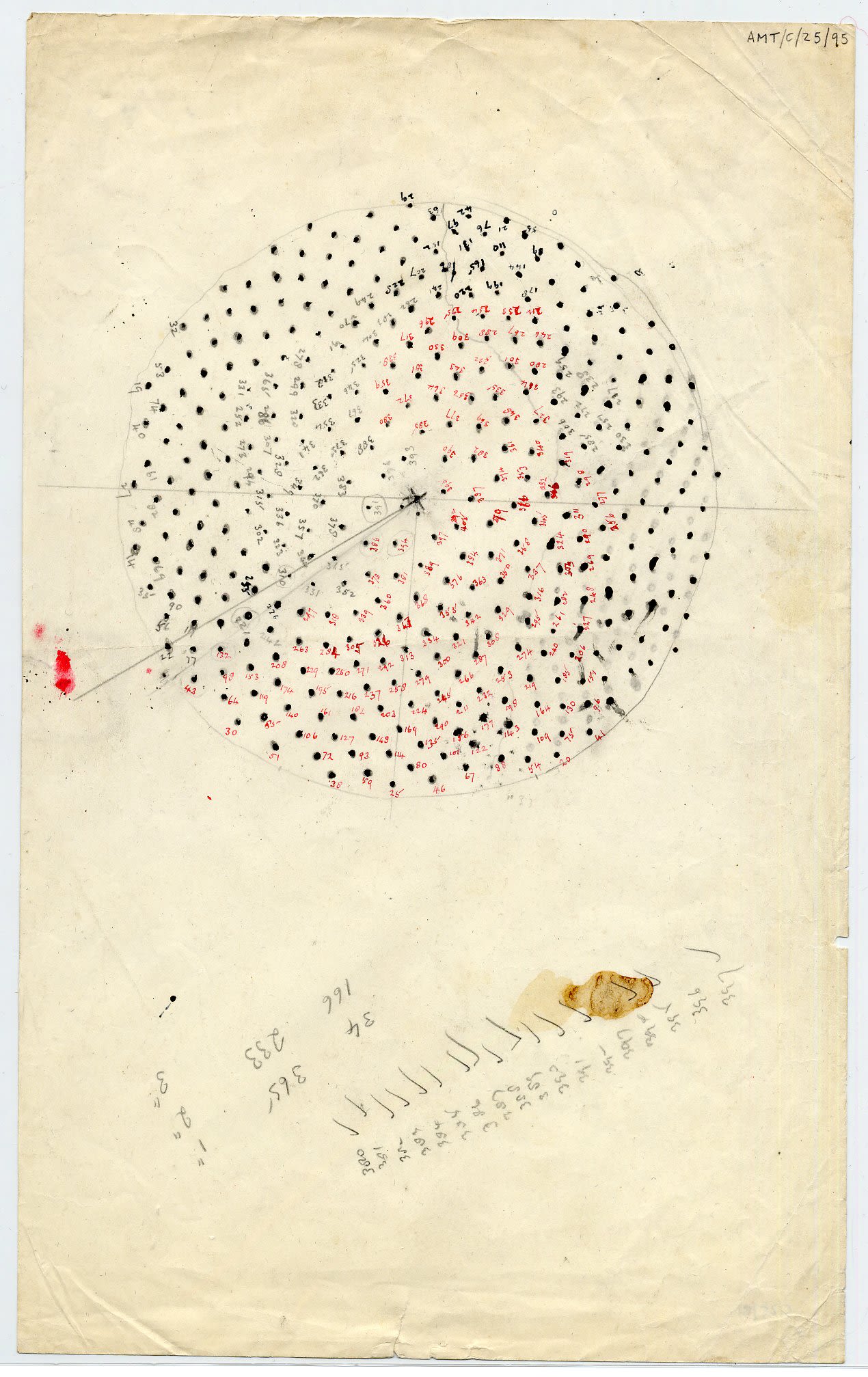

A new work by Sir Antony Gormley (Trinity 1968) has been installed at King’s College Cambridge in January 2024. The sculpture, titled True, for Alan Turing, was commissioned by King's as a visible recognition of the life and achievements of Alan Turing (KC 1931).

The work stands 3.7 meters tall and sits at the heart of the College, between Gibbs Building and Webb’s Court. It is made from 140 mm thick rolled Corten steel, a material frequently used by the artist, including for his most well-known work The Angel of the North.

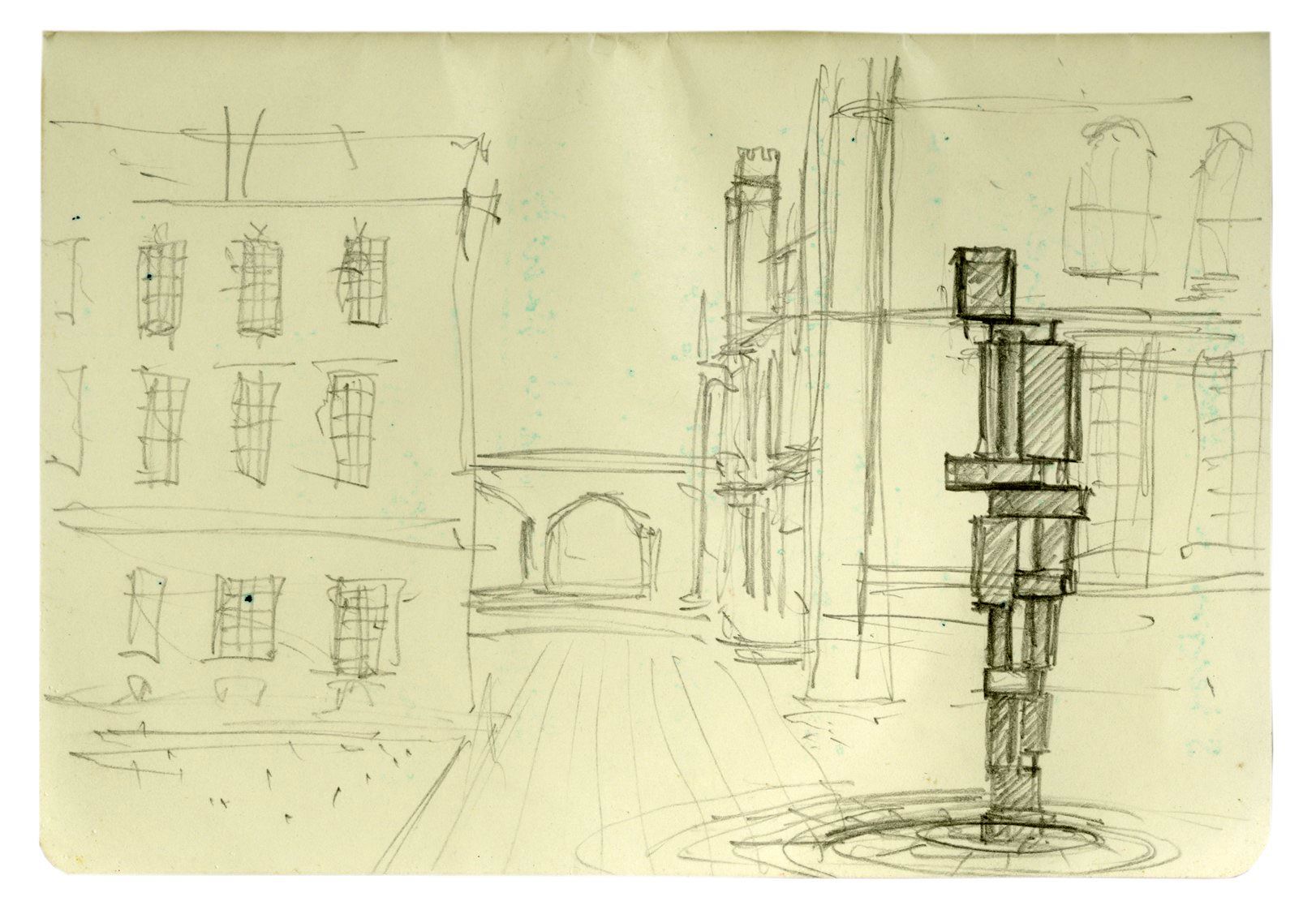

A preparatory drawing for True, for Alan Turing. Courtesy of the Antony Gormley Studio.

A preparatory drawing for True, for Alan Turing. Courtesy of the Antony Gormley Studio.

Alan Turing’s work on mathematics, computing, cryptography and biology continue to impact on the world today. His codebreaking work at Bletchley Park was virtually unknown at the time of his death in 1954 but is now celebrated through blockbuster films and books. His prosecution for homosexuality at a time when it was subject to criminal charges and vicious prejudice means that Turing has become an important icon in the history of gay emancipation and the long, ongoing difficult history of the public acceptance of homosexuality in Britain.

Speaking at King’s, Antony Gormley observed that “Alan Turing unlocked the door between the industrial and the information ages. I wanted to make the best sculpture I could to honour a man who was pivotal in changing the course of all our lives. It is not about the memorialisation of a death, but about a celebration of the opportunities that a life allowed.”

True, for Alan Turing, prior to installation. Image © the artist

True, for Alan Turing, prior to installation. Image © the artist

Commenting on the materials used in the sculpture’s construction, Gormley noted “Corten contains 1% of copper which means it will oxidise over time, forming a rich red rust surface. The sculpture’s relationship with time and weather is an integral part of its character.”

“I want this work to be something that the life of the college lives with and that will be a continual source of questioning, of projection, a marker of an elusive relationship to a person and our evolving time.”

Antony Gormley

The sculpture can be seen from a variety of viewpoints and sits at the junction of routes through the College travelled daily by staff, students, members of the College and University and Cambridge residents. The College will also make the sculpture accessible to visitors and school groups through pre-arranged bookings and on designated occasions such as Open Cambridge days.

The College is hugely grateful to everyone who has contributed to this project and supported the installation of this extraordinary artwork, especially Cambridge City Council, whose enlightened attitude means that the sculpture will give food for thought and pleasure to countless generations to come.

“Antony Gormley’s sculpture is designed to reflect both Turing’s brilliance and his vulnerability. At the same time the sculpture also embodies the transformation of the industrial into the information age. Alan Turing played a crucial part in this transformation, one that continues to reshape our world today.”

"I had to lunch today the Fellowship candidate who seems much the cleverest on paper ... He is excellent – there cannot be a shadow of doubt..."

John Maynard Keynes on Alan Turing, 1935

School days and Cambridge

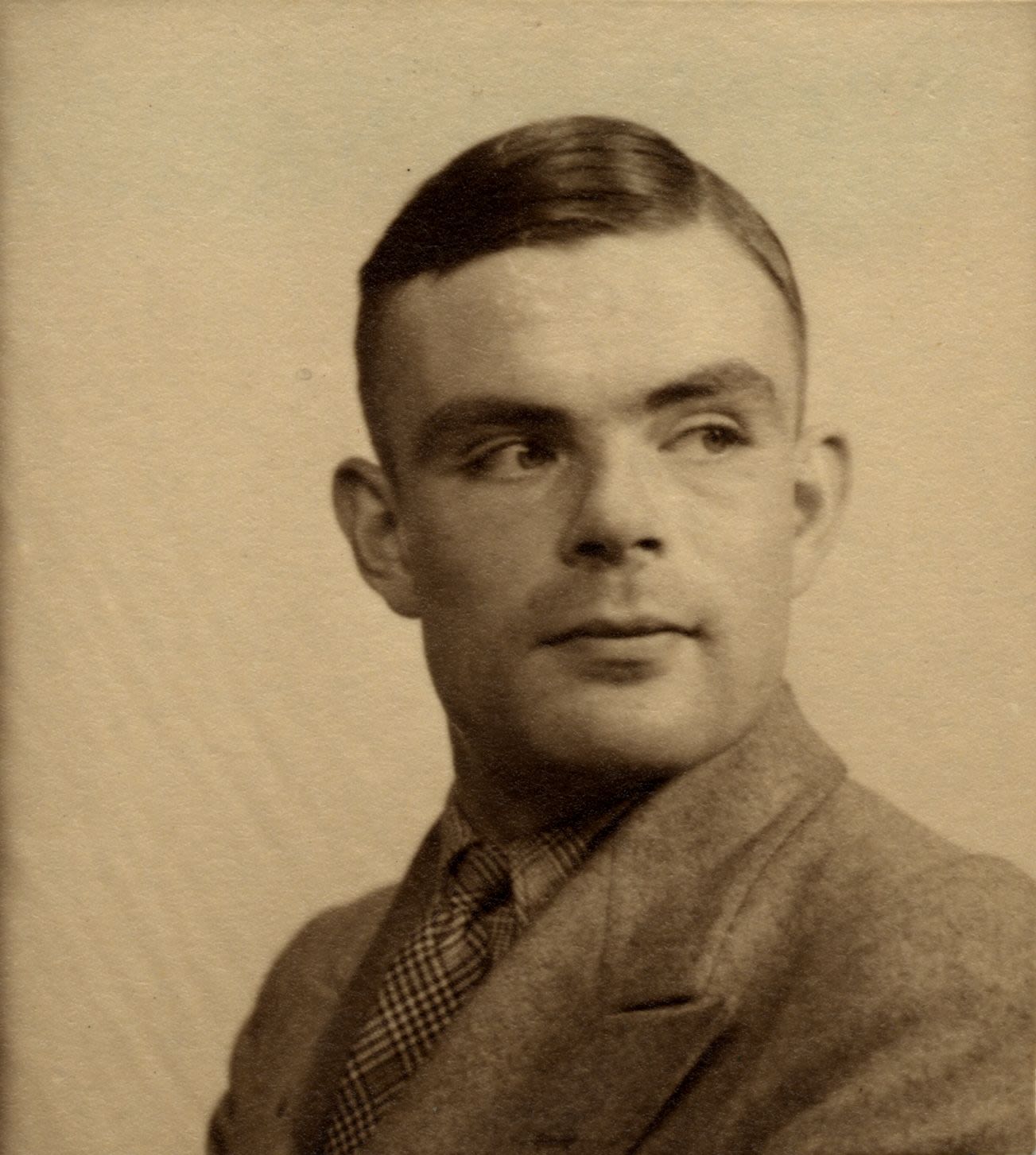

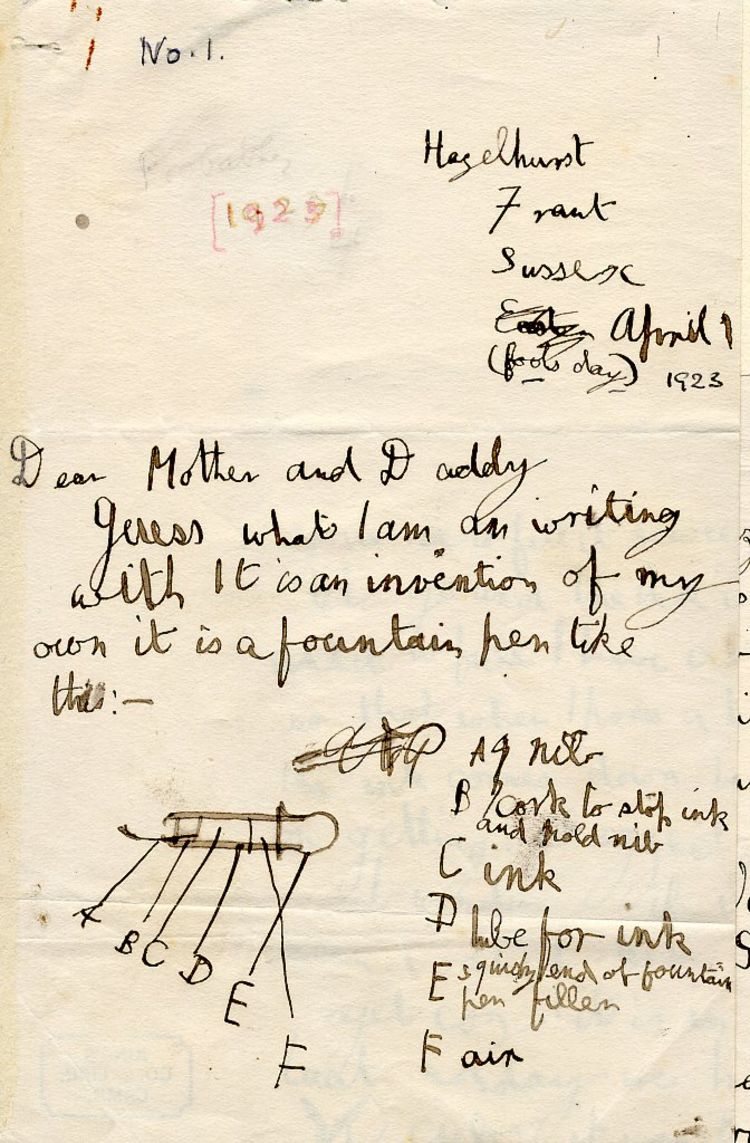

Alan Mathison Turing was born on 23 June 1912, at Warrington Lodge, Warrington Avenue, London to Julius Mathison Turing and Ethel Sara Stoney. He attended Hazelhurst preparatory school then Sherborne School, and his schoolboy letters to his parents reveal his interest in mathematics and chemistry, often including his latest inventions.

He came up to King’s College Cambridge in October 1931. He received a First in Part II of the Mathematical Tripos in 1934 and was made a Fellow in 1935 for his work ‘On the Gaussian Error Function’. He remained a non-resident Fellow of the College until 1952.

Economist John Maynard Keynes was a King's Fellow during Turing's time here, and was a member of the Electors to Fellowships Committee. He wrote to his wife Lydia on 11 March 1935 'I had to lunch today the Fellowship candidate who seems much the cleverest on paper ... He is excellent – there cannot be a shadow of doubt ... Turing his name’

Turing attended Max Newman’s Part III lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics in Spring 1935. These concluded with an outline of David Hilbert’s call for an answer to the question ‘Was mathematics decidable’? Newman encouraged Turing to consider whether there was some mechanical process which might be applied to a mathematical statement to ascertain whether or not it was provable.

Throughout 1935 and into 1936 Turing worked on his proof with Newman’s guidance. Determined to specify a ‘definitive method’, he described a machine (the ‘Turing Machine’ as it became known) working with a paper tape bearing printed symbols. What was the most general type of process this machine could perform?

This breakthrough in abstract mathematics provided the core concept for the later development of computing: the practical physical embodiment of an electronic machine supplied with logical instructions to perform any number of operations.

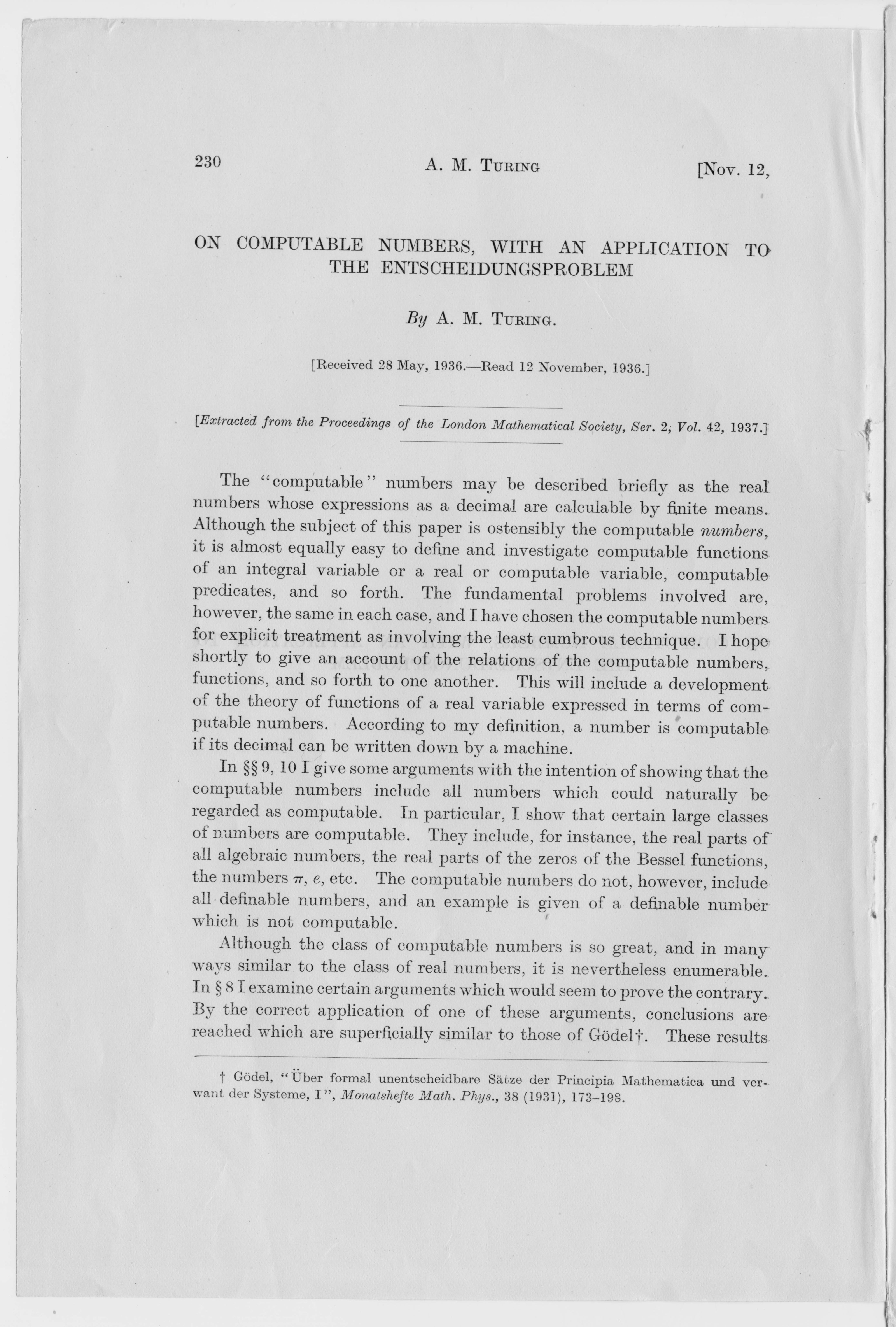

Turing’s famous article ‘On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entsheidungsproblem’, in the process of answering Hilbert’s question, defined what we now know as the programmable computer, then called a ‘universal machine’.

Letter from Alan Turing to his parents, written when he was 11 years old (AMT/K/1/1)

Letter from Alan Turing to his parents, written when he was 11 years old (AMT/K/1/1)

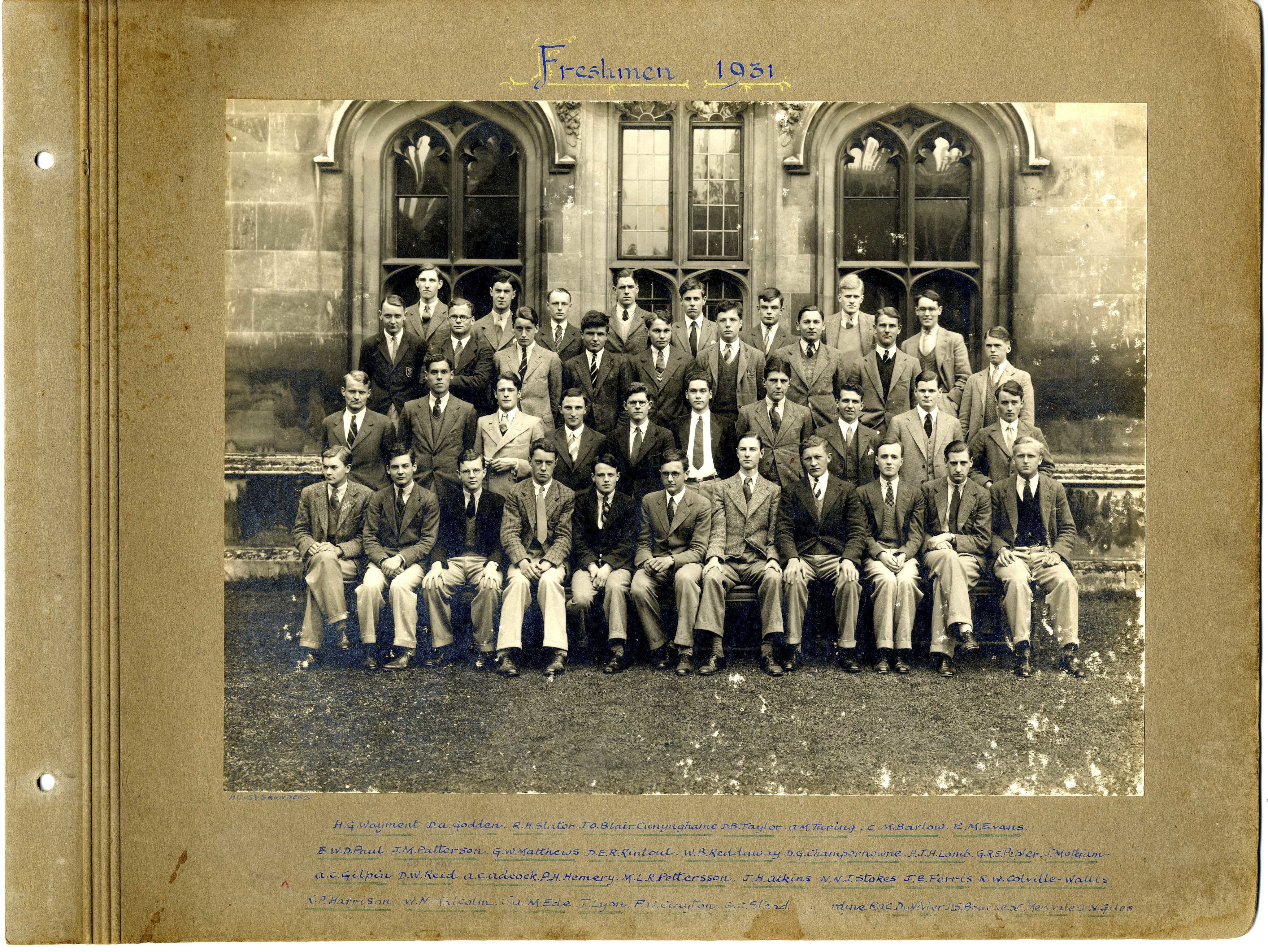

King's College matriculation photo 1931. Turing is in the back row, third from right (KCAC/1/3/6/1/1/1)

King's College matriculation photo 1931. Turing is in the back row, third from right (KCAC/1/3/6/1/1/1)

First page of 'On Computable Numbers' (AMT/B/12)

First page of 'On Computable Numbers' (AMT/B/12)

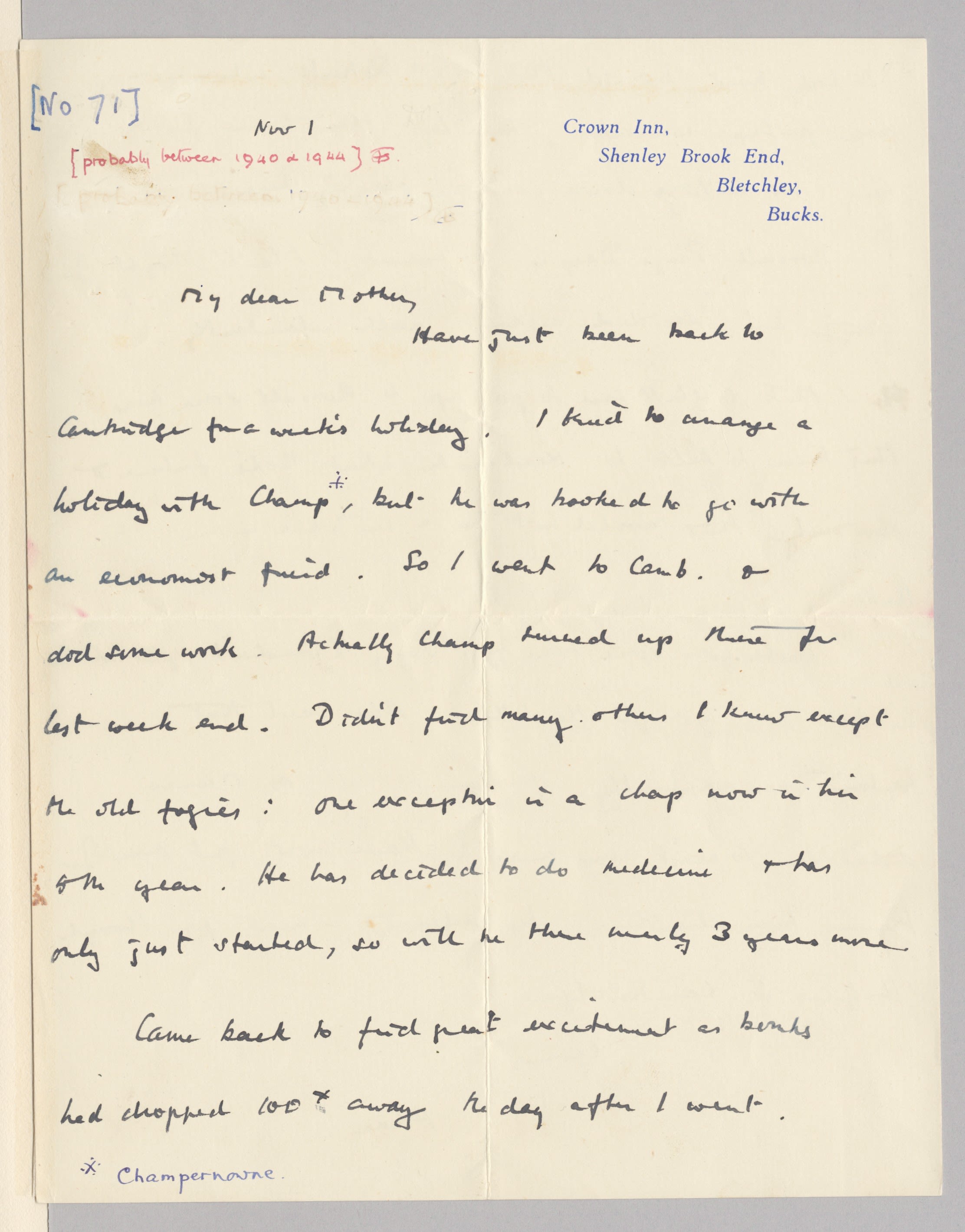

A letter from Alan Turing to his mother Sara, from Bletchley (AMT K/1/71)

A letter from Alan Turing to his mother Sara, from Bletchley (AMT K/1/71)

Alan Turing at a three mile race in Walton, Surrey, 1946. He finished second. (AMT K/7/8)

Alan Turing at a three mile race in Walton, Surrey, 1946. He finished second. (AMT K/7/8)

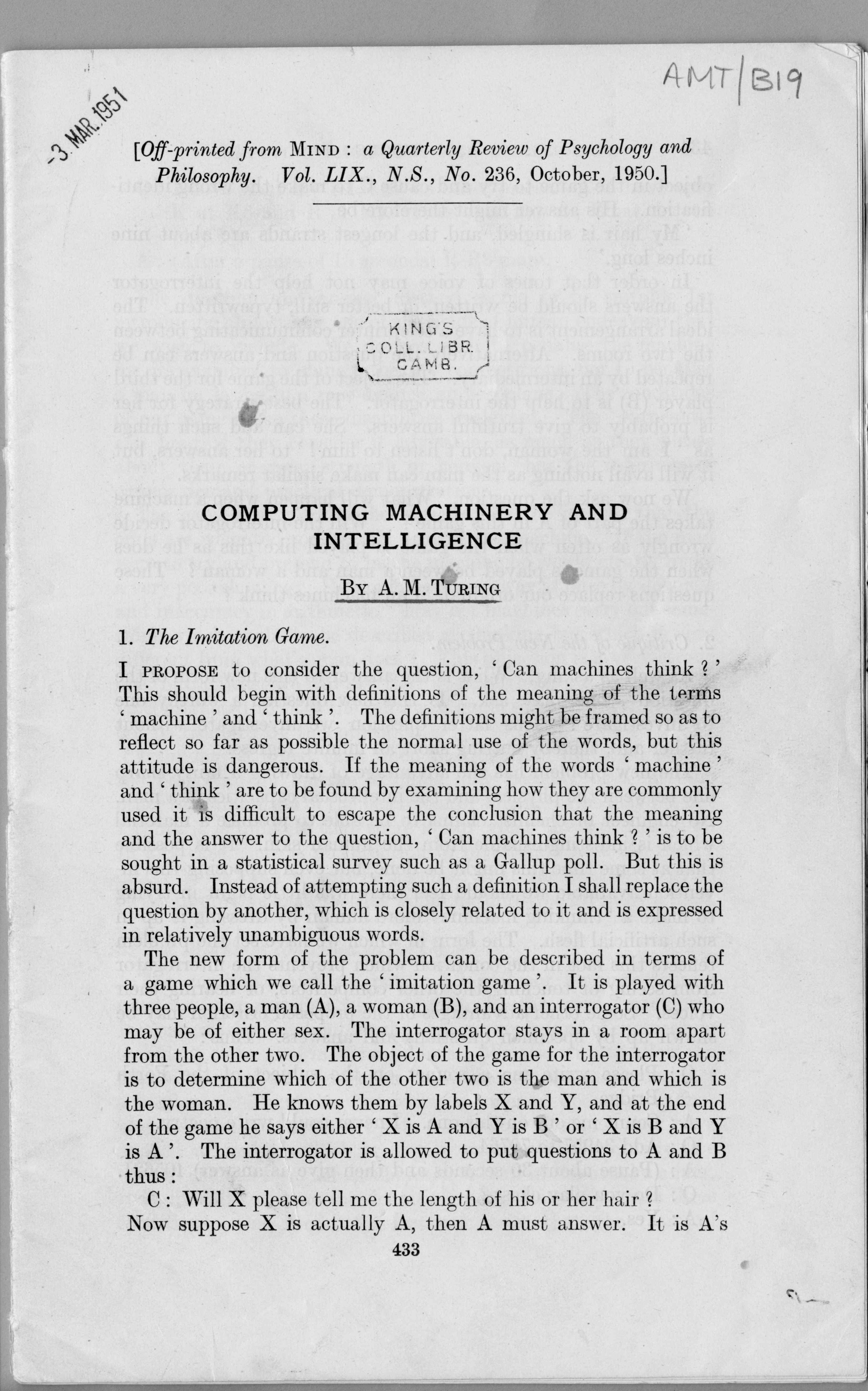

Turing's paper on 'Computing Machinery and Intelligence' published in 'MIND: a Quarterly Review of Psychology and Philosophy' (AMT B/19)

Turing's paper on 'Computing Machinery and Intelligence' published in 'MIND: a Quarterly Review of Psychology and Philosophy' (AMT B/19)

Bletchley Park and Artificial Intelligence

The completion of his research into Hilbert’s Entscheidungsproblem in 1936 coincided with the decision to study at Princeton University with Alonzo Church. It was during this time that Turing’s deep and important paper Systems of Logic Based on Ordinals, published in 1939, was developed.

At the outbreak of the Second World War Turing joined the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park. He developed electronic technology to increase the speed of the mechanical operations that were performed thousands of times every day in decoding intercepted German messages. So well-kept were the secrets of the place that the importance of the Bletchley work was not fully realized until the 1970s when the research documentation (held in the US and UK national archives) was made public. Those working at Bletchley, such as Turing, were allowed to correspond with family and friends but never wrote about their work.

After the war Turing worked at the National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in Teddington, and took up long-distance running (ending his earlier dislike of outdoor pursuits). He was awarded an OBE in 1946.

At the NPL Turing’s technical design for the architecture of the Automatic Computing Engine (the ‘ACE’) was accepted in 1946. Frustrated with the slow and limited progress on building the full-scale ACE, he resigned in 1948 to take up the position of Deputy Director of the Computing Laboratory at Manchester University, while still supervising students at King's. In the late 1940s and 1950s he continued to research, write and broadcast on the emerging discipline of computing. His contribution was wide-ranging, across such issues as programming, neural nets and artificial intelligence.

Turing’s seminal philosophical paper on artificial intelligence, ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’, was written in 1950. For the first time in print he outlined the ‘Turing test’ for the proof or otherwise that a computer could be the mechanical analogue of a brain, which he called ‘the imitation game’. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1951.

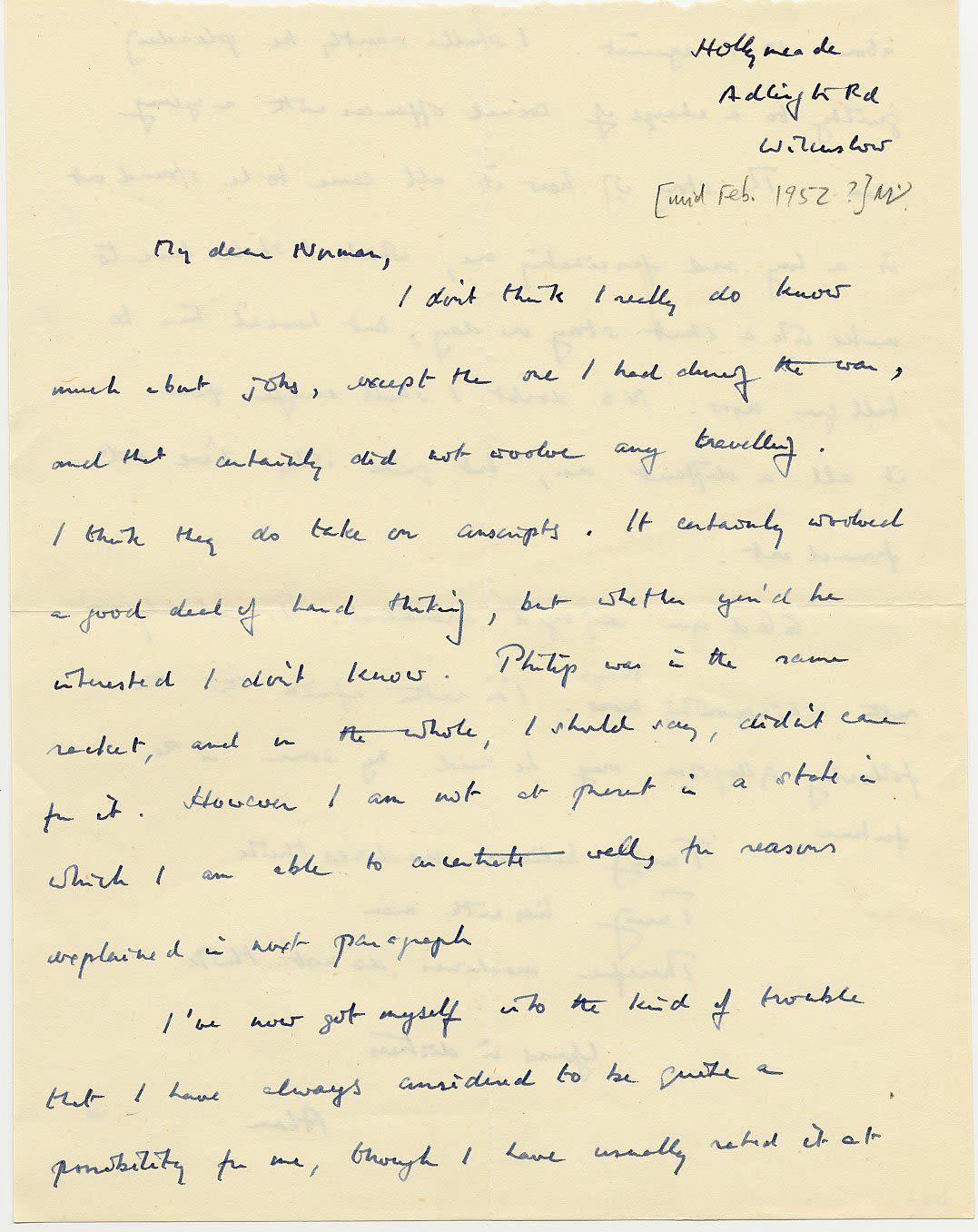

"I've now got myself into the kind of trouble that I have always considered to be quite a possibility for me, though I have usually rated it at as about 10:1 against.

I shall shortly be pleading guilty to a charge of sexual offences with a young man...No doubt I shall emerge from it all a different man, but quite who I've not found out."

Alan Turing in a letter to Norman Routledge, 1952

In 1952 Turing made a straightforward statement about his sexuality in connection with a theft of money from his home, apparently willing to be a martyr for the cause of decriminalising homosexuality. Both he and the man he was in a relationship with were charged with 'gross indecency'. The guilty plea that his brother talked him into saved his mother from having to learn the truth through a trial.

Given the choice between imprisonment and probation, which was conditional on him accepting hormone treatments commonly referred to as 'chemical castration', he chose probation. His conviction led to the removal of his security clearance, meaning he could no longer continue consulting on cryptography for the British government, and he was denied entry into the US.

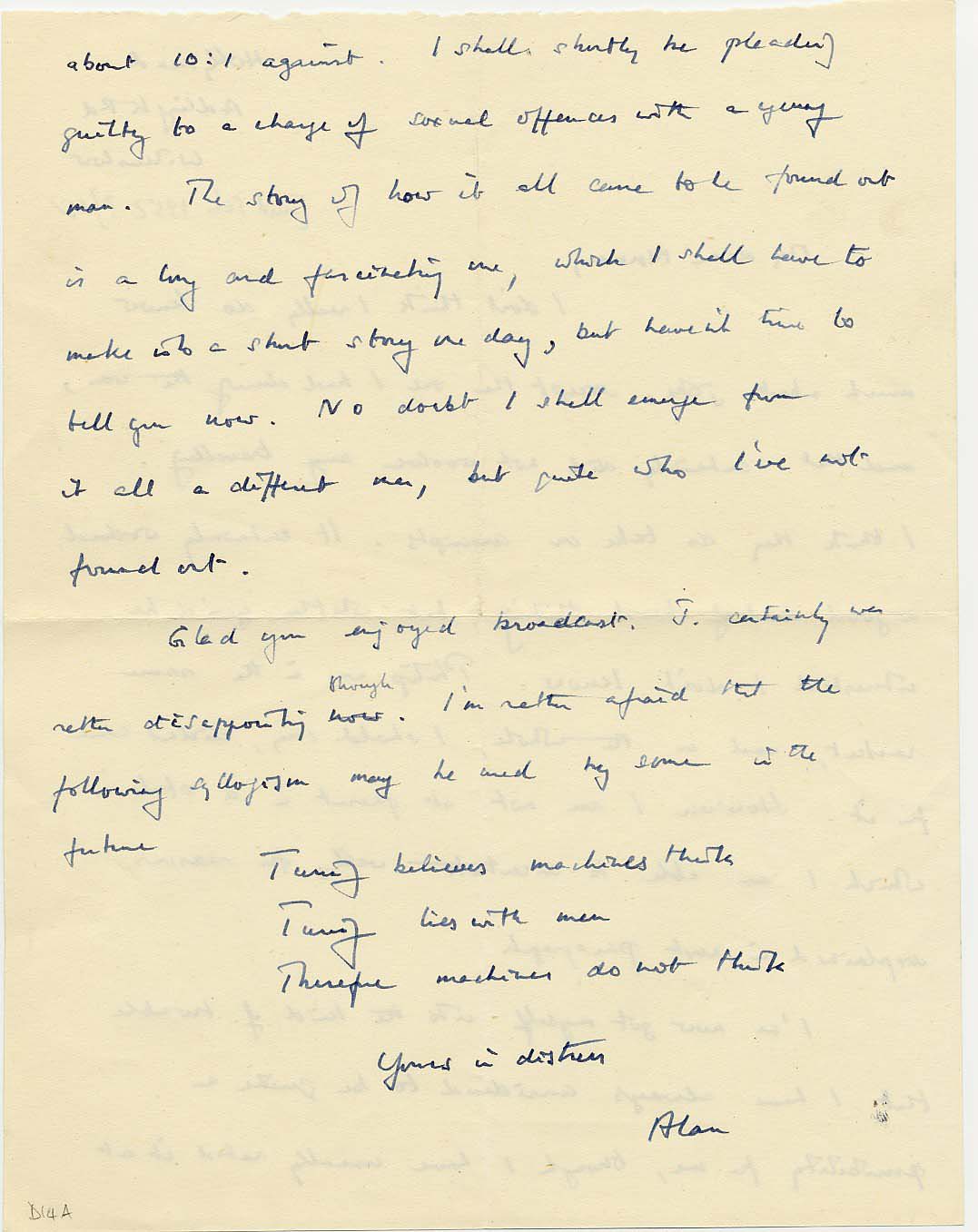

Despite the difficulties in his personal life, Turing continued his work and began to develop a theory of morphogenesis, a mathematical theory of organic growth. Turing’s approach to artificial intelligence – a machine ‘learning’ from its existing state, its electronically stored experience and its programme – could be applied to the study of how a plant ‘knows’ to grow in a particular pattern, based on its existing state of growth, the environmental conditions, and its biologically stored ‘programme’.

He began researching morphogenesis, the growth of cells, in order to discover how the development patterns of the embryonic tissue could be described in chemical terms. He concentrated on the study of phyllotaxis, which is the arrangement of leaves on the stems and florets on the heads of plants. In 1952 his paper on morphogenetic theory was published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society.

Alan Turing died at his home in Wilmslow, Cheshire on 7 June 1954 at the age of 41.

Page 2 of Alan Turing's letter to Norman Routledge, 1952 (AMT D/14a)

Page 2 of Alan Turing's letter to Norman Routledge, 1952 (AMT D/14a)

Diagram from Turing's 1952 paper on morphogenetic theory (AMT C25)

Diagram from Turing's 1952 paper on morphogenetic theory (AMT C25)

About the artist

Antony Gormley (b 1950, London) is widely acclaimed for his sculptures, installations and public artworks that investigate the relationship of the human body to space. His work has developed the potential opened up by sculpture since the 1960s through a critical engagement with both his own body and those of others in a way that confronts fundamental questions of where human beings stand in relation to nature and the cosmos. Gormley continually tries to identify the space of art as a place of becoming in which new behaviours, thoughts and feelings can arise.

Gormley’s work has been widely exhibited throughout the UK and internationally with exhibitions at the Musée Rodin, Paris (2023); Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg (2022); Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar (2022); National Gallery Singapore, Singapore (2021); Schauwerk Sindelfingen, Sindelfingen (2021); Royal Academy of Arts, London (2019); Delos, Greece (2019); Uffizi Gallery, Florence (2019); Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia (2019); Long Museum, Shanghai (2017); National Portrait Gallery, London (2016); Forte di Belvedere, Florence (2015); Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern (2014); Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Brasilia (2012); Deichtorhallen, Hamburg (2012); The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg (2011); Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria (2010); Hayward Gallery, London (2007); Malmö Konsthall, Sweden (1993) and Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark (1989).

Permanent public works include the Angel of the North (Gateshead, England), Another Place (Crosby Beach, England), Inside Australia (Lake Ballard, Western Australia), Exposure (Lelystad, the Netherlands), Chord (MIT - Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA) and Alert (Imperial College London, England).

Gormley was awarded the Turner Prize in 1994, the South Bank Prize for Visual Art in 1999, the Bernhard Heiliger Award for Sculpture in 2007, the Obayashi Prize in 2012 and the Praemium Imperiale in 2013. He was made an Officer of the British Empire (OBE) in 1997 and was knighted in the New Year’s Honours list in 2014. He is an honorary fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, an honorary doctor of the University of Cambridge and a fellow of Trinity and Jesus Colleges, Cambridge. Gormley has been a Royal Academician since 2003.